Nature in Japanese art

Dr. Ricard Bru

Autonomous University of Barcelona

Japanese culture has been shaped and defined by strong ties with the physical environment, where it has developed over the centuries: an extensive territory of significant climactic differences and considerable seismic activity in which the generosity and beauty of nature have played a very prominent role. Both the ancient ethnic religion – Shinto – and the poetry anthologies dating from the 8th century show how the Japanese people’s profound empathy towards nature has become one of the main idiosyncratic traits of their culture. Moreover, as an aesthetic expression of culture, Japanese art has left some exquisite testimonies of that. Just like in the past, today, in a Japan that is wholeheartedly embracing technology, it is practically impossible to ignore the subtleties of the constant and permanent changes of the seasons. That is why, throughout history, all sorts of idealised and emotional representations have emerged, from the imposing Mount Fuji to the most humble flower petals. Together, they form a vast repertoire of images adapted to all registers, styles and formats, which has ended up playing a central role in the history of Japanese art.

Although Shinto – an animistic form of worship – refers us to a distant past, the observation and aesthetic veneration of idealised representations of nature did not spread among the country’s upper classes until some time around the Heian period (794-1185), when aristocrats, artists and poets far removed from rural settings began to express, through brushstrokes, an intellectualised and refined view of flowers, plants, birds and landscapes. From that time on, the ultimate expression of the intimate relationship between nature and the human gaze would be the representation of the passing of time through the different seasons, which was an inexorable reminder of the melancholic beauty of the ephemeral world. In this respect, The Tale of Genji, a famous work of Japanese literature written by Murasaki Shikibu in the 11th century, is a constant ode to the pleasures of nature and the continuous change of the seasons, to the golden leaves of autumn, to the full moon of August, to the dew, to the plum blossom, or to the sound of the wind through the pine trees. “It sometimes troubles me to think about the transience of things, always in perpetual change”, said prince Genji, “but all I need is the chance to look at the flowers of a new spring in order to cling to visible reality, even though I know it is only a whimsical dream.” In its day-to-day life from that time on, the Japanese court got used to living enclosed in palaces surrounded by poeticised nature: “Within the limits of my own garden”, added Genji, “I have sought to bring in what I can of the seasons: the flowering trees of spring, the plants that reach their peak of beauty in autumn, the humming sound of insects that evokes balmy summer nights...” It was not only the court that surrounded itself with a garden or a small fragment of nature, however. All interiors began to be adorned with fusuma sliding doors and folding screens that reproduced colourful yet stylised nature expressing an abundance of beauty and emotion.

Over the years and centuries after the Heian period, artistic representations did not cease to become enriched by further propositions and increasingly diverse formats, techniques and styles. Thus, from the 13th century and under the influence of Zen Buddhism, continentally inspired motifs of flowers and birds began to be introduced, and these were exclusively depicted in black Chinese ink (sumi-e). It was a new type of painting that responded to new times marked by the Ashikaga shogunate and samurai patrons, who saw in the austerity and self-sufficiency of Zen Buddhism an attractive model to pursue. Paintings like the one of Mount Fuji made in a single brushstroke by the Zen monk Etsusō Myōi at much later dates display one of the essential traits of Zen Buddhist painting, in which, through essential and intuitive strokes, landscapes were hinted at rather than being complete (MEB 507-1). However, besides in works by the Buddhist monk painters, nature was present in a much broader array of art forms, not only in paintings on horizontal and vertical scrolls (emakimono and kakejiku, respectively) and on interior doors and walls, but also on all sorts of everyday elements and objects, from silk kimonos to lacquers, ceramics and even paper, correspondence and poetry. Great artists like Kanō Eitoku, Tawaraya Sōtatsu, Kanō Tan’yū, Itō Jakuchū, Maruyama Ōkyo and Ogata Kōrin, who were followers of trends as diverse as the Tosa, Kanō, Rinpa, Nanga and Maruyama-Shijō schools, as well as countless others, many of whom were anonymous, have passed down to us through the centuries their own views of nature, that from distant times was felt and experienced intensely in Japan.

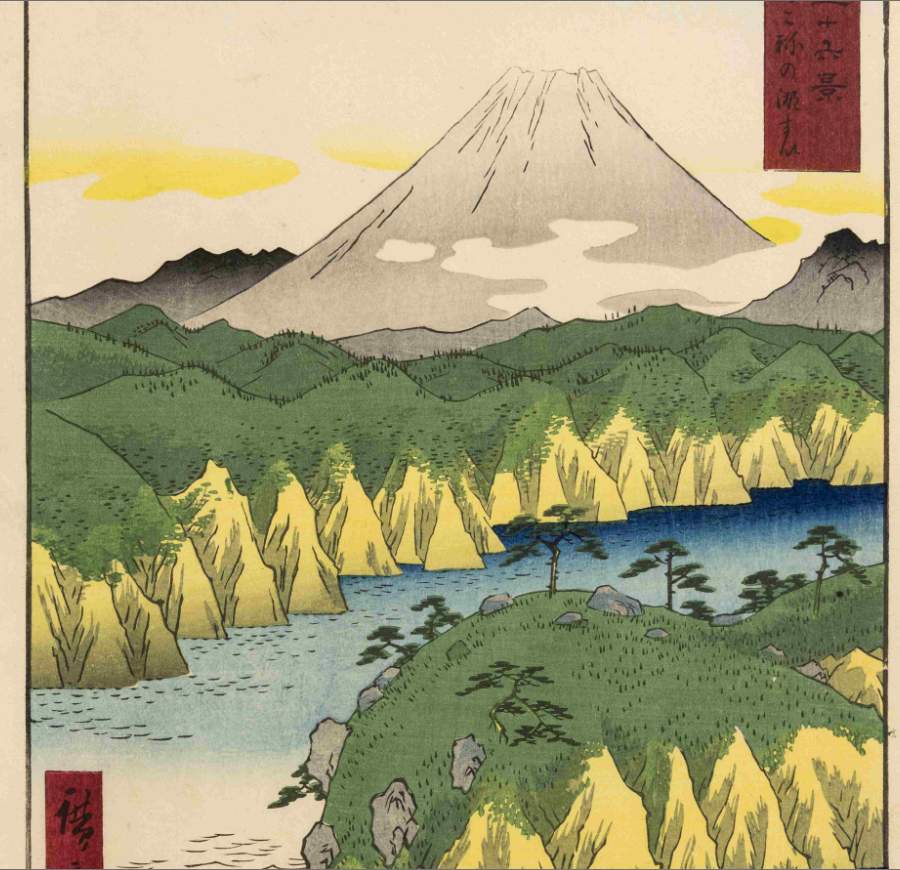

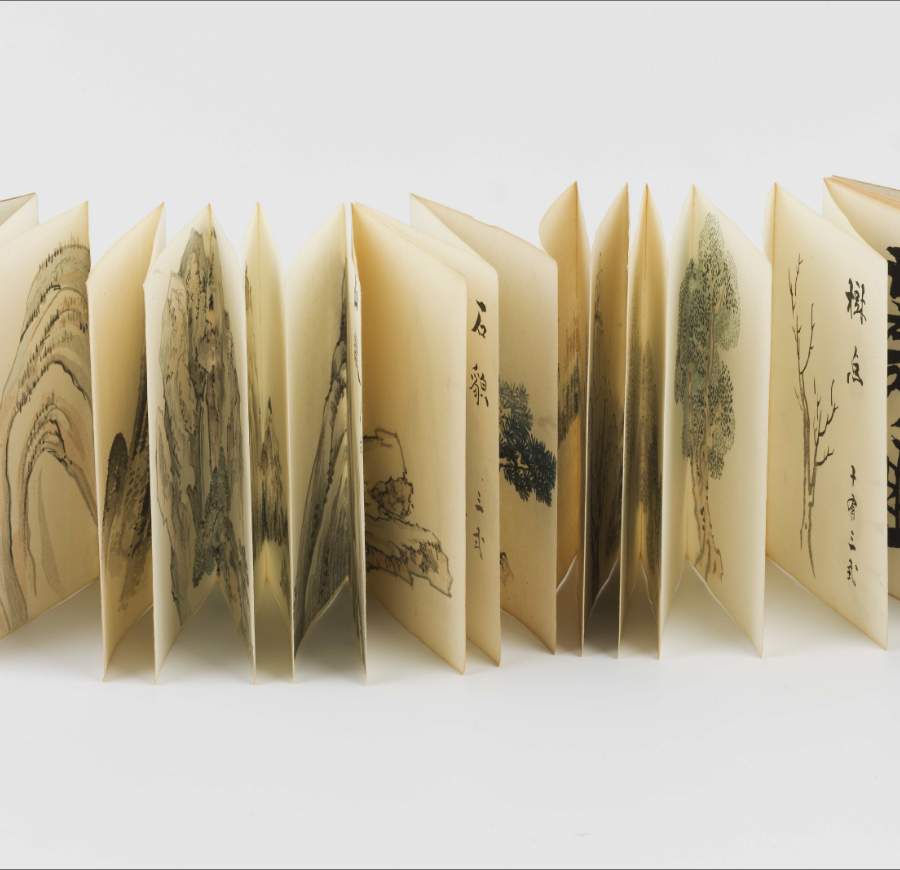

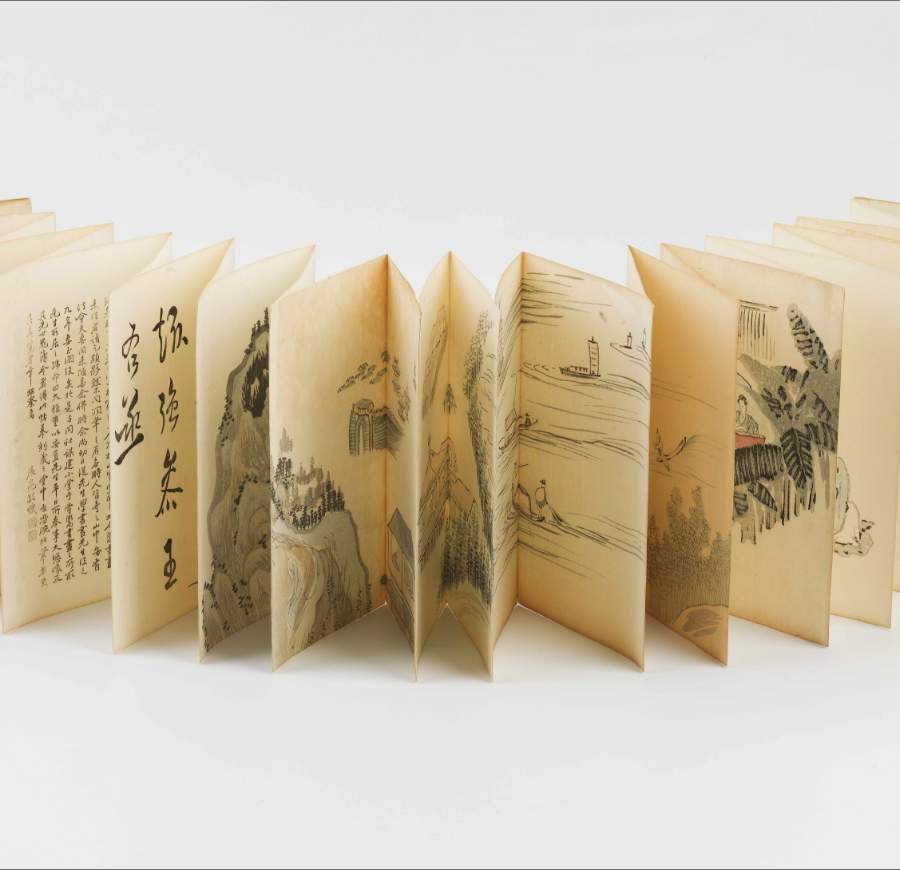

The decoration of a small ceramic piece could become the ideal medium for evoking common places that had been made popular through literature and poetry, such as the blooming cherry trees of Yoshino and the reddish autumn leaves falling into the waters of the famous Tatsuta River (MEB 121-122). Likewise, ancient kimonos were covered in patterns as varied as flying cranes, rough waves or flowers such as the lilies growing around the eight-planked bridge (yatsuhashi) described in the 9th century in The Tales of Ise. This wealth of art forms is clear to see in the MCM’s Japanese collection, with pieces as diverse as the katabira (MEB 414-1858), an ancient summer kimono (kosode) decorated with embroidered chrysanthemum flowers from the mid-Edo period (1600-1868), or the illustrated books or prints that give us an insight into the different approaches taken to nature. Some examples can be found in the proliferation of manuals for artists, which taught them how to depict flowers, birds, trees and mountains: from the two volumes of Taigadō gafu (MEB 152-830), posthumously copied circa 1803 by Sō Geppō from an illustrated scroll painted by Ike no Taiga, and the Ippitsu gafu volume by Katsushika Hokusai (MCM 7 02), created for those wishing to learn how to draw with a single brushstroke, to the landscapes and the famous views of Mount Fuji disseminated by artists of the ukiyo-e school in the 19th century, such as those by Utagawa Hiroshige (MEB 506-3).

Enthused by the discovery of Japanese prints, in 1887 Vincent van Gogh did a portrait of the art dealer Père Tanguy (Rodin Museum, Paris) surrounded by woodblock prints by Utagawa Kunisada and Utagawa Hiroshige, including the view of a cherry tree in bloom dedicated to the great warrior Minamoto no Yoshitsune in Ishiyakushi (MCM 7 07), which belongs to the series “Famous Sights of the Fifty-Three Stations” (1855). This cherry tree actually made Van Gogh dream of being able to travel to Japan and is one that he would almost certainly have recalled when discovering the trees in bloom in Arles in early 1888. Not without reason did Japanese art captivate Western artists no sooner had Japan opened its borders in the mid-19th century. Indeed, throughout the centuries, Japan had known how to look at, read and feel nature from a viewpoint that was both emotional and aesthetic, and all of its art was imbued with such sensitivities.

Related pieces

You may also be interested in...

Valdivia Statuettes

Dr. Ramiro Matos

In the Valdivia settlements, both on the surface and in the excavations, the dominant cultural material is high-quality ceramics, with varied form and decoration.

Further informationThe figure of Krishna

The Folch collection has a fine selection of sculptures representing Hindu deities. We will focus on one of them, Krishna, to try and approach the complexity of these beliefs, which have the third-largest number of followers in the world.

Further informationCrosses of Ethiopia

Dr. Ewa Balicka-Witakowska, PhD

The small pendant crosses are worn by every Ethiopian Christian but especially by women, often as a complement to a cross-tattoo on the forehead, hand or neck.

Further information