In a context in which inequalities and male chauvinism are still very prevalent, there is evidence that, among young people, changes are taking place towards a freer and fairer sexuality. The lack of adult guidance can generate scenarios in which the discourse of violent and biased sexuality is reproduced, but a new generation is emerging that is challenging the established order, and this may be somewhat shocking, but it is a victory.

The collective imaginary around sexuality determines its constituent elements: identity, sexual preferences or certain practices in shared sexual relations. However, it is a cross-cutting issue that affects everyone and is much more widespread and more important than what is generally believed. Bodies and our knowledge of them, self-esteem, affection, the relationships we build, decisions about how we take care of ourselves, imaginaries, desires and pleasure are some of the key elements that are interwoven to shape the experience of sexuality. Thus, it transcends the individual, becoming a social and cultural issue that plays an important role in shaping and organising societies. Moreover, it is slowly, gradually, heterogeneously and complexly constructed from birth to death, through multiple physiological, emotional and relational, but also contextual, moral, political and even economic elements.

There is a social consensus that we should pay attention to sexuality, but only as it is constructed during certain stages. That sexuality in adolescence is risky and irresponsible is not only a consensus, but also a long-standing constant. What today, in the eyes of adults, are proper, sensible and careful practices and attitudes, were once extremist, risky or crazy for other adults.

If we consider what happens during adolescence as an integral process, we can see that it is a key stage in the construction of a person’s identity, their relationships and the consolidation of values. All of this at a time when the foremost expression of curiosity, doubts, a sense of belonging and difference to the familiar world is developed. If we apply this to the realm of sexuality, it is natural, common and healthy for the desire to explore and experiment to emerge. It is also true that worries and uncertainties often arise, often without knowing where to land, without finding a space that the adolescent understands and that meets their needs. Far from finding it, they often come up against walls that raise the alarm and measure their behaviour in terms of risk, thereby pushing this search for information or guidance into other channels. Often, the gap between the adult imaginary on adolescent sexuality and the reality of this sexuality reflects adults’ lack of capacity to guarantee adolescents’ rights.

The study La sexualidad de las mujeres jóvenes [The Sexuality of Young Women], carried out by the Women’s Institute in 2022, shows how information is only provided by parents in 8% of cases and how other reference points and sources of information are sought, which are usually mainly friends and the internet. Although the search for information is a positive indicator of their curiosity and autonomy, the lack of guidance can generate scenarios in which the hegemonic discourse of sexist, violent and biased sexuality is reproduced in terms of the representation of bodies, practices and experiences. Access to real and comprehensible information is therefore imperative to foster the development of a critical eye in the midst of a flood of information they find in different channels.

The young population must learn; and learning, more often than not, is through reference points, modelling and information. We are passing on the whole system that we created and sustained to them, while also asking them not to reproduce it. We want them to change, to live and relate differently, but we are offering them the same things as before. The same inequalities, discriminations and power relations, the same systemic failings.

Young people’s sexuality reflects the expectations of a society that does not wish to acknowledge its flaws and structural inequalities.

Young people’s sexuality explicitly represents this entire phenomenon: it reflects the expectations of a society that does not wish to acknowledge its flaws and structural inequalities, while at the same time it must prove to be transgressive in relation to these flaws that it has been incapable of overcoming over the last few decades.

What do we find if we look directly?

To begin with, we must recognise that we are still in a context in which inequalities and male chauvinism are still very prevalent: violent relationships continue to exist, taking on specific forms in the young population that are even more difficult to identify. We find, for example, that one in four women feel unsafe on the street on their way home; that the main source of discrimination against girls (more than 50%) is their physical appearance; and that more than half of them (57.7%) admit to having had unwanted sexual relations at some point. But we cannot forget that violence and discrimination are not part of sexuality, they only try to call its free expression into question and, even so, they have less and less ground.

Moreover, if we take a closer look at reality, alongside these elements that point to the survival of the models projected by the adult world, we also find evidence that major changes are taking place towards a freer and fairer sexuality.

According to the FRESC 2021 survey, 26.3% of girls aged 15 and 16 report to have suffered gender-based violence at the hands of their intimate partner. But it also shows that 64.2% of boys and 71.8% of girls state that they feel satisfied in sexual terms and that 77.1% of girls and 80.2% of boys had used some form of contraception in their last sexual relationship. In other words, young people are increasingly identifying gender-based violence, enjoying their sexual relations more and more, exploring their desire and seeking out means of self-care.

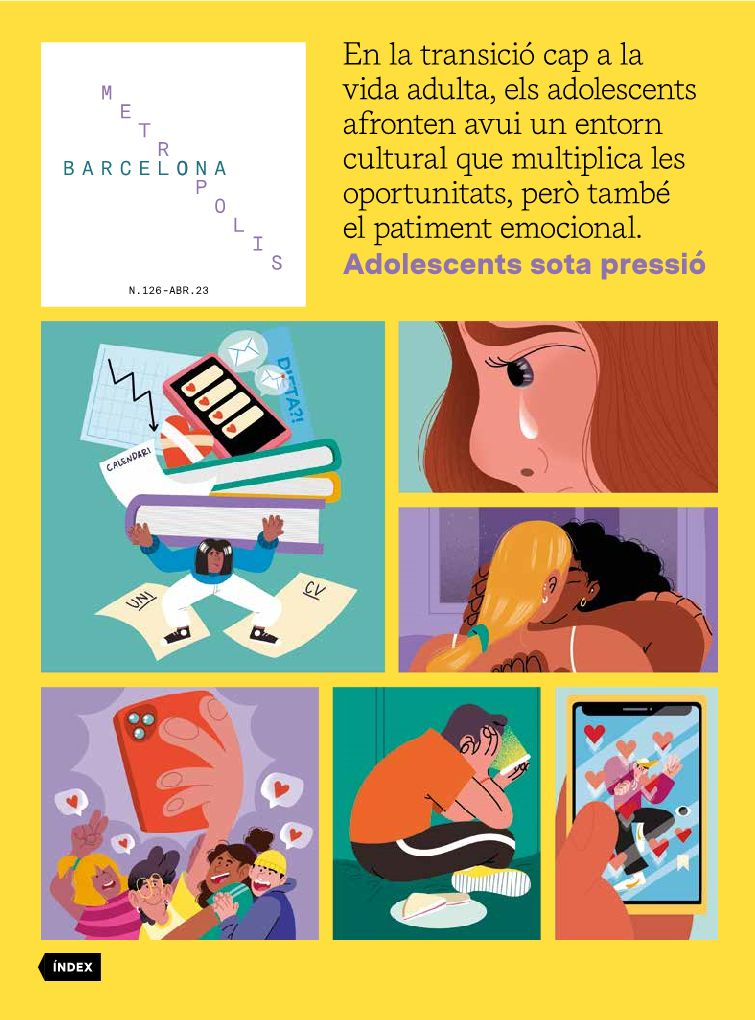

Illustration. ©Genie Espinosa

Illustration. ©Genie EspinosaWhile some generations have not yet let go of beliefs such as the romanticisation of suffering and sacrifice, another generation is emerging that challenge the established order.

We are dealing with a generation that is concerned over, active and interested in self-care, understood not only as an individual act, but also as a collective one. Young women are actively engaged in advocating for their right to decide as an exercise in individual and collective sovereignty. They understand that health is a broad concept that includes physical, mental and affective-sexual health in a holistic manner, and they want to nurture all of them. They understand that everything also depends on their environment and they think in terms of sustainability. Young women demand to be able to decide about their bodies, care and relationships. To decide which methods are most appropriate at each life stage and to choose with whom to share experiences and how to do so. Young women are concerned about pleasure, in all its facets.

While some generations have not yet let go of values and beliefs such as the romanticisation of suffering and sacrifice, another generation is emerging that wants to enjoy itself, is interested in self-awareness, meeting their needs and making them possible in a sustainable manner, challenging the established order. And this might disconcert us to some extent, but it is a victory as people who feel, live and experiment, whose goal is the pursuit of pleasure, satisfaction and wellbeing.

And this quest for wellbeing does not involve attaining a specific, socially acceptable position in which to settle, but rather a path towards self-awareness that is constantly under construction. In fact, it is on this path of learning and discovery where spaces for listening, the right to make mistakes, the right to have doubts and the opportunity to ask questions without being judged are essential. This should be our premise and our foremost concern. Not so much what they are doing or not doing, but what we are doing and not doing when it comes to guiding them on this path.

Our main concern should not be so much what young people are doing or not doing, but what we are doing and not doing when it comes to their guidance.

Every year, more than 7,000 young people and adolescents visit the Sexual Health and Education Centre for Young People (CJAS), concerned over – and looking after – their sexual health. In 2021, 132 people received psychological counselling specialised in gender-based violence, some 1,200 young people were screened for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and 2,041 emergency contraception pills were dispensed to prevent possible unwanted pregnancies. It is clear that young women have found a way to fill the gap left by our inability to guarantee these rights and to ensure access to the spaces, tools and strategies needed to deal with such a complex issue that even as adults we have not resolved.

How can we be there?

Let’s ask them. There are questions that condemn collectives, which determine their immovable position and condemn them to continue reproducing the same inequalities. Conversely, there are others that support the movement, which give it agency and challenge its capacity for transformation.

Let’s listen to them. We are living in a historical period that has shattered the fantasy of a supposed stability and control that we thought we had. Faced with absolute uncertainty in almost every realm of their lives, and with the few emotional and relational management tools they have received, young people have coped with admirable maturity and resilience. And we cannot just sit back and listen to what they are telling us.

A sound goal, if we are to understand what our role might be, is to offer them a framework in which they can be informed, make choices and enjoy their sexualities, whatever they may be. The positive experience of sexuality depends on all of these factors, as well as the opportunity to develop and achieve them in a relaxed and comfortable manner. In other words, it can be said that the degree of freedom and equity in a population’s sexuality is a reliable indicator of the democratic health and individual and collective rights of a society.

References

Sánchez-Ledesma, E., Serral, G., Ariza, C., López M. J., Pérez, C. and collaborating group of the FRESC 2021 survey. La salut i els seus determinants en adolescents de Barcelona. Enquesta FRESC 2021. Barcelona Public Health Agency, Barcelona, 2022: http://ow.ly/GwX350MSCmt

Pinta, P. and Vázquez, S. La sexualidad de las mujeres jóvenes en el contexto español. Percepciones subjetivas e impacto de la formación. Ministry of Equality, Secretariat of State for Equality and against Gender Violence. Women’s Institute, 2022: http://ow.ly/PFbH50MSCnk. Open in a new window

The newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter to keep up to date with Barcelona Metròpolis' new developments