The rise, fall and revival of the Plaça Reial

- Urban visions

- Feb 20

- 11 mins

Few places in Barcelona have been as dynamic and as changing, as central and at the same time as hidden, as the Plaça Reial. It started out as a brothel, to later become a convent and, subsequently, a square that encapsulated the longings of the Barcelona bourgeoisie. An elegant place, located in the centre where well-to-do families resided until the Eixample neighbourhood was built, that became a hotspot for riffraff and that hit rock bottom in the final decades of the 20th century. This whole trajectory, until the square’s revival at the dawn of this century, reveals much of the history of the Ciutat Vella neighbourhood.

The square with no status

In the Middle Ages, where the Plaça Reial now stands, the Viladalls brothel was run, the only one that could legally operate in the city. The establishment gave its name to the street that ran alongside it, which from the 14th century was renamed Carrer del Vidre, on account of the glass foundry set up there. Once the brothel and foundry had gone, and following the Spanish War of Succession, Capuchin monks were offered the land, who had lost their home in the fighting. The convent that was built was dedicated to Santa Madrona and opened in 1723, with an entrance on the Rambla.

That Barcelona was a place where people lived on top of one another and had no public spaces. The idea to make it a square came from the Captain General of Catalonia, Antonio Ricardos, who proposed moving the Capuchins to the abandoned monastery of Sant Pau del Camp. Almost thirty years later, a journalist from the Diario de Barcelona newspaper wrote about the proposal, sparking a debate that convinced the Government to build a square there. The Capuchin convent was therefore demolished in 1822. Unfortunately, the following year French troops occupied the city, putting an end to the Liberal Triennium, and ordered its reconstruction, now with a point of entry on the new Carrer de Ferran street.

Santa Madrona was not set ablaze during the Burning of the Convents rampage in 1835. However, the community was expelled and the convent was fitted out for other purposes. It was the headquarters of the newspapers El Constitucional and El Vapor. It was the Santa Àgueda school and the Lancasteriana school for homeless children. It was a military barracks, and the second Civil Guard barracks and garrison in Catalonia. And the Caputxins theatre, later turned into the Teatre Nou. Finally, in 1848, the convent was knocked down and the foundation stone of the future square was laid, designed by the architect Francesc Daniel Molina.

View of the Plaça Reial in 1893.

View of the Plaça Reial in 1893.© Photographic Archive of Barcelona / Author: Hauser i Menet.

Around 1850 it was popularly known as the Plaça de les Dides, because female domestic workers met soldiers in search of companionship there.

The bourgeois dream

The square’s first formal name was Plaça de Caputxins, but from 1850 it began to be called Plaça Reial. Work began on the future Passatge Madoz passageway, on the property known as Casa Plandolit, the city’s most luxurious mansion at the time. In those years beggars were already laying their heads there, children engaged in stone-throwing fights, and the first petty thieves reared their head. It was popularly known as the Plaça de les Dides [Wet Nurse Square], because female domestic workers met soldiers in search of companionship there.

The Farmacia del Globo pharmacy, the Bazar de los Andaluces and the El Águila department store soon opened their doors, as well as the best cafés and restaurants of the era, such as Café Restaurante de Paris, the first to serve ice cubes and iced coffee. And Café Suizo, known for being the place where the Parellada rice recipe was born. Café Restaurante de Europa, Café del Universo and Café Español also opened. The most famous was Café Restaurante de Francia, with a French chef who had worked for Emperor Napoleon III. He would become the grand educator of the Barcelona bourgeoisie, who he would teach to eat and drink.

The square was completed in 1864. It measured 55 by 83 metres, with porticoed arcades 5.5 metres wide. The buildings had been influenced by the Palais Royal in Paris, with attics concealed behind a stone balustrade. Despite appearing to be, the new square was not square. Nestled between the Rambla and the surrounding labyrinth of asymmetrical alleys, one side had one more arcade than the others. Four years later, when the revolution of 1868 broke out, the square was renamed Plaça Nacional [National Square], and did not recover its name until 1875. At that time, a fountain was purchased in Paris, dedicated to the Tres Gràcies [Three Graces]. And two streetlamps, designed by a young architect called Antoni Gaudí. And it had illustrious visitors, such as former US President Ulysses S. Grant and Empress Elisabeth of Austria. Corros also came into being, which were improvised political debates where everything could be discussed, dubbed the Barcelona Hyde Park.

Plaça Reial fulfilled the ideals of the local bourgeoisie; exotic palm trees were even planted in 1883.

Plaça Reial fulfilled the ideals of the local bourgeoisie; exotic palm trees were even planted in 1883. The most important newspapers of the time set up their headquarters there, including El Diluvio, La Vanguardia, El Barcelonés and El Progreso. And political clubs were opened, from where the city was governed, such as the Círculo Fusionista [Fusionist Circle]. This pleasant and tranquil world was changed by a bomb that exploded in 1892, taking one person’s life and wounding others. In those days, Furest shirtmaker’s would open, but their customers would soon move to the Eixample, and Furest with them.

The working-class square

In the early 20th century, the opening of the Ritz hotel was contemplated. However, the Plaça Reial was no longer the same; well-to-do families had left and the city centre was packed with workers and late-night entertainment venues. In 1902, another iconic monument was unveiled, which no longer exists today. It was a fountain christened the Fuente Mágica [Magic Fountain], twenty-seven years before the Montjuïc one, which replaced the Three Graces. It spewed and spouted cascades of water in an array of colours, illuminated by 96 high-voltage arcs of light. The bourgeoisie would visit the fountain on their way out of the Liceu opera house, and then hang out at one of the restaurants on the square. But the proximity to the Barri Xino [“Chinese Quarter”, a generic reference to all foreigners, as the area was inhabited by immigrants from other parts of Spain or from abroad. Known today as the Raval.] was changing the neighbourhood.

During World War I, it became a refuge for foreign refugees who got by begging. In the wake of the war, inflation and rising prices sparked huge workers’ protests. In 1918, housewives rallied together during the Women’s Strike. One year later, the Pedagogical Museum of Natural Sciences, founded by the taxidermist Lluís Soler i Pujol, was opened. And shortly afterwards, the Sunday Philatelic Exchange and the Glacier Café Restaurant, two of the square’s emblematic spots. By 1925 it was already clear that the magic fountain did not work, so the Three Graces fountain returned.

During the Second Republic, it was renamed Plaça Francesc Macià. Then it was home to the Bretaña bar, the basement of which hosted a macabre cabaret called La Cova de les Bruixes [The Witches’ Cave]. Also present were the Gran Cabaret Francès and the Automático bar, with no waiters and where everything worked with vending machines activated with small change. The first cocaine dealers also appeared, offering one-gram cones. With the outbreak of the Civil War, the square bore witness to patriotic events and artistic evenings. During the Events of May it came under anarchist control and, later, a PSUC [Unified Social Party of Catalonia] office was opened there. The square did not escape the bombings either, notably during the attack of 23 November 1938, when one of the bombs was dropped on the street Carrer de Colom.

American sailors helped bring about the square’s revival, which became the hub of Barcelona’s recreation during the 1950s and 1960s.

In March 1939, the new authorities renamed it Plaça Reial. In the post-war period it lost its bourgeois nature once and for all, and it became a dirty and dismal place, full of boarding houses and sublets. Establishments in those years included a drapery, a fruit warehouse, and two factories producing umbrellas and handkerchiefs. This changed as of 1941, when the Canarias bar opened, a pioneer in organising beer drinking contests. In the 1950s, the square began to fill with people attracted by the tankards of beer and the battered squid. Capitalising on the success reaped by the Canarias bar, it soon came to have competitors. The first was the Vivancos brewery, followed by the Taberna del Rey, the Bonet breweries (which later became the Colón and Ambos Mundos bars), and the Brindis bar (the future Jamboree), where the Bodega Andaluza (the future Los Tarantos) began.

The Brindis bar was one of the first venues of the Sixth Fleet of the United States, whose sailors frequented the square. Americans went to the Zodiac, to the Tyrol brewery, Montparnasse and Texas, bars with waitresses dedicated to them. Perhaps the establishment most closely linked to the Sixth Fleet was El Tobogán, the first USO headquarters in Barcelona, a body responsible for entertaining troops stationed outside the country.

The Americans helped bring about the square’s revival, which became the hub of Barcelona’s recreation during the 1950s and 1960s.

Aerial view of Plaça Reial, circa 1988.

Aerial view of Plaça Reial, circa 1988.© Photographic Archive of Barcelona / Author unknown.

The years 1985 and 1986 were dire; scuffles between leftist youth groups and skinhead gangs were common at the weekend

The abyss of drugs

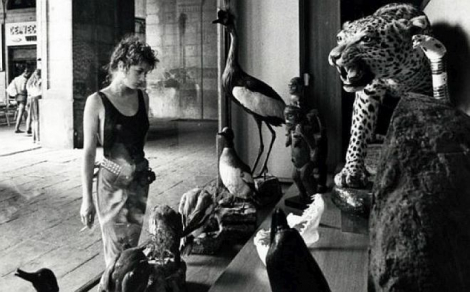

The second half of the 1960s saw a steady rise in crime in the square, especially with regard to drug dealing. The number of robberies also soared. Common thieves or “fences” stole coats and luggage, and sold them off there in a sort of flea market. Hippies from around the world also appeared, passing through on their way to Ibiza, who occupied benches and smoked marijuana. The square also saw artists like Ocaña and Nazario, as it was very close to the gay centre of recreation, in the area below the street Carrer d’Escudellers.

Karma opened in 1978, followed by Sidecar three years later. In those days there were dozens of drug dealers in the square, a market initially in the hands of gypsy clans residing in the neighbourhood. However, in the late 1970s, it became an international business. Neophyte users who went to buy doses there found the most adulterated drugs in Barcelona.

The square’s remodelling began around that time, which had been entrusted to the architects Federico Correa and Alfonso Milá, who banned the circulation of vehicles, got rid of the flower beds and paved the square. The result was an austere square, very much in vogue at the time. Despite the controversy it sparked, it did not yield the expected results. The square had changed, but those would be its worst years, when it was said to be like the yard of the Model prison. In these circumstances, the novelist Maria Aurèlia Capmany and the architect Oriol Bohigas, as well as the singer-songwriter Lluís Llach, the musician Marc Almond, the artist Lindsay Kemp, the Argentine writer Copi, and the singer Jaume Sisa moved there. The theory was, in principle, that changing the residents would restore the peace, but that didn’t work either.

The years 1985 and 1986 were dire; scuffles between leftist youth groups and skinhead gangs were common at the weekend. On 22 February 1988, one of the most dramatic incidents took place, when gangs of Africans clashed with gypsies wielding sticks, knives and machetes fighting for control of the drug market. The following weekend, a religious fanatic stabbed two transvestites. Later, a consignment of adulterated drugs killed 25 drug addicts. As a result, a police van was permanently stationed in the middle of the square.

The Olympic Games were a mirage, and when they were over, it returned to the way it was before. However, AIDS and clashes between gangs drove the dealers out, heroin went out of fashion and the square witnessed a revival.

Present-day view of Plaça Reial.

Present-day view of Plaça Reial.© Pepe Navarro.

Showcase for tourism

In the early years of the 21st century, the square became a tourist attraction. New pavement cafés and restaurants appeared, the few remaining prostitutes disappeared, and the beggars moved elsewhere. The opening of the Ocaña bar and the five-star Hotel DO were a catalyst in its revival. With the porticoed arcades completely taken up by bars and eateries, and the central fountain by tourists, the lost peace was restored. It came at the cost of the disappearance of the former residents, whose bargain rents had prevented them from leaving before. Now they were directly driven out by the prices asked of them. The former boarding houses, transformed into private homes, became tourist apartments.

The square has changed but the stigma lives on, at least among certain generations. Young people, unfamiliar with the square’s dark past, frequent it as a meeting place. For them it is a fashionable spot, shared with tourists. Most of the hoteliers are not very keen on the City Council’s management, who complain that they want to get rid of the pavement café-bars and restaurants and reduce their opening hours, although they argue that it was precisely them that facilitated the square’s revival. The debate moves between letting the square remain on the sidelines, or allowing it to be a showcase for tourism. We will have to determine whether the evils caused by the remedy are worse than the disease. It all depends on the people of Barcelona, on whether they make the square their own again or they let it become a victim of its success.

Publications

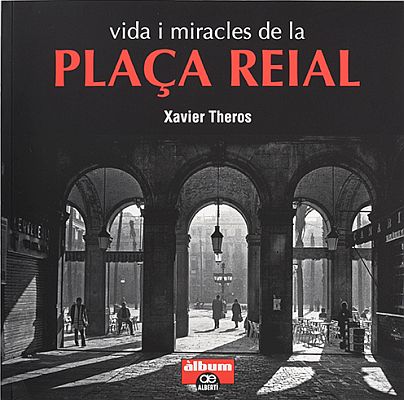

Vida i miracles de la plaça ReialCoedició: Albertí Editor i Ajuntament de Barcelona, 2019

Vida i miracles de la plaça ReialCoedició: Albertí Editor i Ajuntament de Barcelona, 2019

The newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter to keep up to date with Barcelona Metròpolis' new developments