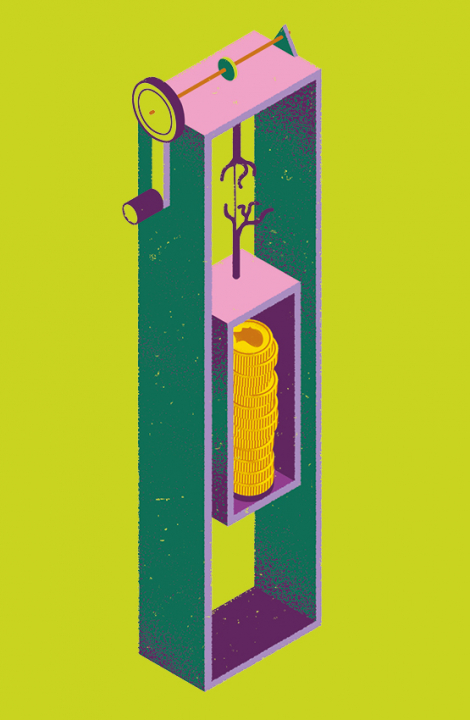

The broken elevator

- Dossier

- Feb 20

- 13 mins

Something is happening in global society. Citizens today are showing, with social unrest in many parts of the world, a palpable discontent after many years of stability. Economic inequality and social mobility are the two main ingredients of this explosive cocktail.

The tricky role of social memory

Societies’ memory is very fragile. Our capacity to remember is tainted by numerous biases that prevent us from seeing reality according to a more or less rational perspective. As soon as certain historical coordinates settle, our perception of time comes to a standstill.

However, the forces that push societies are precarious and change always preys on them. When this happens, we realise the inaccuracy of our predictions. We note that our frameworks of perception are always rooted in the past (Bourdieu, 1972). We are very bad at predicting, above all, in times of deep social change.

And there is no doubt that we are living in a time of profound transformations. The world is literally on fire. In recent months there have been outbreaks in Ecuador, Haiti, Iraq, Chile, Bolivia, Hong Kong, Lebanon and France. Although Spain is not experiencing such a situation, the fact remains that 15M showed the face of somewhat weary citizens. What is happening across wider society to cause such social unrest? Why after so many years of stability has social upheaval resurfaced?

In this paper we will attempt to provide an explanation in this regard. We will also be bold and endeavour to put forward possible solutions. To this end, we will start with the connection between two very popular concepts: economic inequality and social mobility. As we know, the first relates to the concentration and distribution of income in a given society, while the second helps to measure how many people climb, remain in the same social position or descend the social ladder compared to their parents.[1] We believe that, by working together with these two dimensions, we can reach, if not an improvement, a possible path of investigation.

The Great Gatsby Curve

In 2009, when the high impact of the global financial crisis began to make itself felt, a book entitled The Spirit of Level. Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better was published. Written by Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett, two social epidemiologists, it was an unprecedented bestseller. It showed the correlation between income inequality and economic mobility by means of data from eleven countries. The most unequal countries had less intergenerational social mobility.

However, it was in 2012 when Alan Krueger, chair of Barak Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers, made the Great Gatsby Curve popular in a speech at the Center for American Progress. Using this curve, he endeavoured to illustrate the strong link between inequality and social mobility. In a deeply unequal world, life chances are monopolised by a small number of privileged sectors. Income inequality inevitably brings lower social mobility in its train, and when it is wide, it stands in the way of social progress for the less privileged classes, who are inevitably excluded.

[1] The people that ascend the social ladder in relation to their class of origin are part of upward mobility. People who descend the social ladder compared to their parents are part of downward mobility. Those who maintain the same social class are designated immobile (or social reproduction).

The Great Gatsby curve already demonstrated in 2012 that equal opportunities, the liberal principle of contemporary societies, were in jeopardy.

The Great Gatsby Curve is not inconsequential for the following reason. It shows that equal opportunities are in jeopardy, a liberal principle governing contemporary societies. The meritocratic ideal is built on a precondition: all citizens in a society must have an identical chance of being selected to occupy the positions of greater responsibility once they have demonstrated their potential and their talent. Thus, the efficiency of contemporary capitalism is under threat, as the selection of executives might be following a twisted logic: rewarding less intelligent candidates and hampering those who, with special talent, do not come from a high social status.

Hence a basic problem arises, since any ideology needs a good justification to endure (Piketty, 2019), which poses an obstacle on the road that is difficult to surmount. Without a heavy tax on high incomes that will help us guarantee greater equality in the starting conditions for the less privileged, the soundness of the system cannot be ensured. We exclude a major swathe of the population, making the system flawed, and this is because wide inequality generates an even more adverse effect, i.e. social exclusion. The theory of trickle-down economics, which forecast that rising incomes and investment at the top end of the spectrum would lead to higher incomes at the lower end, finds no empirical evidence to support the claim.

Rise in inequality

In Spain, the evolution of the most renowned measure of inequality, namely the Gini index, has been U-shaped since the beginning of the Spanish industrial miracle up to the present day. When the Stabilisation Plan began, the Gini coefficient was around 40 points. As of the 1970s, it began to fall until it reached, just before the financial crisis, figures below 30 points (Cha and Prados de la Escosura, 2019). It is a trajectory that Spaniards can be proud of; there are hardly any countries in the world that have achieved the goals of modernisation in such a short period of time. Industrialisation, expansion of education, mesocratisation [sustained growth of the middle class], democratisation, secularisation... Each of the milestones that define advanced societies was reached over these years.

However, since then, the Gini index began to grow to almost 35 points. A point must be underlined here. Although the rise in inequality in recent years has not been excessive, in just five years, the crisis has brought us back to figures similar to those of the 1990s. Or put another way, although the increase is not dramatic, it is if we consider the narrow space of time in which it has occurred. While everyone felt the brunt of the crisis, even the well-off, the working classes felt it much more.

In Spain, the social elevator came to a halt: the capacity of our production system to create more skilled employment generation after generation fizzled out.

The evolution of social mobility rates

Considering the same period of time, absolute mobility rates shrunk in the early 1990s among men and, a decade later, they stagnated for women. By contrast, downward mobility stopped and immobile positions remained more or less stable (Marqués Perales, 2015). In other words, the social elevator came to a halt: the capacity of our production system to create more skilled employment generation after generation fizzled out. The amount of skilled employment for new cohorts ceased to be greater than for the former ones. And this has not happened in every country. In some countries, such as the Netherlands, whose upward mobility has not waned, the number of managers and professionals continue to rise generation after generation, as is the case in other countries such as Norway and Sweden.

It should be borne in mind that upward social mobility did not stop growing from 1960 to 1995. The reasons set out for the prolonged maintenance of the social ladder are based on three factors explained below. Firstly, educational reforms opened up the possibility of study to a large mass of people, a great deal more than who had studied in previous years. There is no doubt that the opening of universities and the rise in investment in education bore a very positive effect. Secondly, the economic advancement of their parents, which allowed them to cope with the high opportunity costs. And thirdly, feminisation, first in terms of education and then work. School segregation by gender progressively decreased and women even began to attain better academic achievement than men. Once women were orienting their social mobility strategies towards education, they were successively earning qualified positions in companies and, most notably, in public-sector employment: administration, education and the health system.

A new correlation between inequality and social mobility is emerging in contemporary societies, including Spanish society.

The equation of discontent: high inequality + low mobility

Everything seems to point to a new correlation between inequality and social mobility emerging in contemporary societies, including Spanish society. The equation of discontent is the outcome of a new explosive cocktail created by the rise in inequality and the fall in social mobility. As far as the former is concerned, although it is true to say that individuals do not necessarily have an acute perception of inequality, when inequality gathers the great momentum that it acquired during the crisis, it is no wonder that their awareness thereof is heightened. With regard to the latter, it must be taken into account that individuals do not move along the social ladder in the same way as they did in the past. Since education is the first social mobility route in contemporary societies (Blau & Duncan, 1978; Hout & DiPrete, 2006), many individuals have worked hard to complete their studies. Broken promises. Firstly, for some children who do not find their place in life and, secondly, for parents who see that their efforts (and money) have not borne fruit. On completing their studies, they cannot find a job that matches their qualifications. In such a scenario, it comes as no surprise that backing for institutions is waning (CIS [Spanish public research institute], 2012: study 2.951) and, with them, the bipartisanship that more or less governed our country for so many years. This poses a distinct problem of social legitimacy.

How to turn the situation around

Today nobody doubts that, as a resource allocation mechanism, the market economy delivers benefits for society. At present, there are few who advocate for the end of private enterprise and capitalism. However, we have relied too much on the goodness of its invisible hand. The shifts of contemporary capitalism have generated a scenario more characterised by savings than by economic growth (Piketty, 2013). When the latter reaches significant proportions, changes are inevitably generated and social mobility tears apart the old hierarchies. Nevertheless, when stagnation prevails, family dynasties are formed, and this is when the allocation mechanism proposed by the market continuously fails.

Two routes can be taken: one on the supply side and one on the demand side. The first one is easier than the second; it entails increasing the dimension of the management and professional classes. However, in a period of low growth, that is very difficult to achieve. We do not live in the golden years of Spanish capitalism. If we pursue the demand side, we can try to contain the process of education inflation through more demanding examinations and more expensive enrolment fees.

In our opinion, a possible solution could be to tighten up both routes, but in a very different direction. There is no doubt that social mobility is greater when small businesses become large companies, since they generate a more skilled workforce (Kaelble, 1985). But not only that. We know that big companies also have more streamlined and therefore, a priori, fairer employment systems. Consequently, a resolute policy of business consolidation would be beneficial in terms of social mobility. Channelling greater efforts into technological investment and into fostering organisational efficiency would be timely measures, and given the limited size of Spanish companies, the good news is that there are signs of improvement here. That said, the most positive thing capitalism has emerges from small businesses. In this regard, we must be very aware that large companies drive social mobility, but cripple the celebrated creative destruction (Schumpeter, 1965), which is undoubtedly the best thing the market economy has. On the other hand, the combination of low growth and education inflation calls for a policy of radical democratisation in both the economic and education domains. And combining these two spheres, we consider two possible correlations: firstly, the correlation between social origin and academic performance and, secondly, the correlation with individuals’ class destiny.

Educational inequalities

Income transfers determined by academic achievement have proven to be an especially successful measure. An example thereof is the scholarship awarded by the Junta de Andalucía [Government of the Autonomous Community of Andalusia] called Beca 6000 [6000 Grant], which seeks to “offset the indirect opportunity costs incurred from full commitment to non-compulsory studies, as well as to foster student effort and achievement” (Río and Jiménez, 2014). This type of grant is currently being awarded in Mexico, Brazil, the United States and the United Kingdom. The problem with this type of scholarship is its limited coverage to a small target group.[1] It should be extended and consider all families with low-middle income, especially when their parents have low incomes and they start out from a low level of education. In addition, these types of scholarships should be promoted not only by the State, but by companies through private foundations, as is already done in other countries. Through this type of aid, we could positively discriminate against students who come from less advantaged social classes.

At this point, an important issue must be clarified: academic qualifications are positional goods. What does that mean? It is very simple: their use depends on how many individuals study. Let’s imagine a society whose work structure reaches 20 % of skilled employment. If the number of individuals who have a university degree is 80 % instead of 30 %, it will be much more difficult to find a job matching one’s level of education. Consequently, a scenario of sharp education expansion does not necessarily translate into a rise in social mobility. To achieve this, we have to consider the link between individuals’ academic achievement and class destiny.

[1] The eligible family income to apply for the grant is €7,306.50 for a household of four individuals (Río and Jiménez, 2014).

It is inconceivable that economic elites do not have to account for how they select their workforce.

Access to occupational destiny through education

It is inconceivable that economic elites do not have to account for how they select their workforce, nor is it fair that positions of greater social responsibility be co-opted without being accountable to society. I do not think it is very difficult to make them take part in a broader social project as long as the proposed access channels are clear. Private companies have social responsibilities and although profit making is their primary goal, it should not be their sole objective. Although they should choose those they consider to be the best candidates, those applicants with a certain profile, regardless of their origin, should also have a chance of being selected. In the United Kingdom, the goals of the Social Mobility Commission include appraising the personnel selection processes of large companies, and its recommendations include different areas such as childhood, schools, geographic area and work.

Let’s look at one of its recommendations in the last domain that relates to what we have just said:

“Make socio-economic diversity in professional employment a priority by encouraging all large employers to make access and progression fairer, with the Civil Service leading the way as an exemplar employer.”

(Social Commission, Time For Change: An Assessment of Government Policies on Social Mobility 1997-2017. June 2017).

Considering just the role played by educational inequalities will not yield positive results; we must take into account the role that education itself plays in the class destinies of individuals. Considering both together, perhaps we can set the social elevator in motion, the safety valve of capitalist societies (Hirschman, 1973).

References

Blau, P. M. & Duncan, O. D., The American Occupational Structure. Free Press, New York, 1978.

Bourdieu, P., Esquisse d’une théorie de la pratique, précédé de trois études d’ethnologie kabyle, Droz, Geneva, 1972.

Cha, M. and Prados de la Escosura, L., “Living Standards, Inequality, and Human Development since 1870: A Review of Evidence”. IFCS – Working Papers in Economic History. WH 28438, Universidad Carlos III de Madrid. Instituto Figuerola, Madrid, 2019.

CIS. Opinion poll, July 2012, study 2.951. Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas [Spanish Centre for Sociological Research], Madrid, 2012.

Hirschman, A., “The changing tolerance for income inequality in the course of economic development”. World Development, vol. 1 (12), pp. 29-36. December 1973.

Hout, M., & DiPrete, T. A., “What we have learned: RC28’s contributions to knowledge about social stratification”. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, vol. 24 (1), pp. 1-20 (2006) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rssm.2005.10.001

Kaelble, H., Social Mobility in the 19th and 20th Centuries. Europe and America in Comparative Perspective. Berg, Leamington Spa, United Kingdom, 1985.

Marqués Perales, I., La movilidad social en España. La Catarata, Madrid, 2015.

Piketty, T., Le Capital au XXIe siècle. Éditions du Seuil, Paris, 2013.

Piketty, T., Capital e ideología. Deusto, Barcelona, 2019.

Río, M. Á. and Jiménez, M. L., “Las becas 6000 a examen. Resultados, prácticas, expectativas y oportunidades escolares de familias y estudiantes incluidos en el programa”. Revista Internacional de Sociología, vol. 72, no. 3, pp. 609-632. September-December 2014.

Schumpeter, J. A., Imperialismo. Clases sociales. Tecnos, Madrid, 1965.

Social Mobility Commission, “Time For Change: An Assessment of Government Policies on Social Mobility 1997-2017”. June 2017.

The newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter to keep up to date with Barcelona Metròpolis' new developments