Digital nomads: The new phenomenon impacting global cities

Tourism: The danger of being too successful

- Dossier

- Jan 25

- 14 mins

The touristification of the world is clearly illustrated by the phenomenon of digital nomads – typically individuals who have more purchasing power than the local population, who challenge the ttraditional work model of fixed, in-person work hours by bringing their work to holiday destinations. But what impact does this have on the cultural, economic and social dynamics of these destinations, especially in cities?

Current tourism development in many parts of the world presents us with at least two paradoxes. The first is the paradox of crisis. While many of us love to travel, tourism today poses significant challenges for numerous destinations: a “plague” that results in overcrowding, loss of housing and quality of life for residents, social discontent and strain on public services and their deterioration. This paradox arises, in part, because tourism is an extractive industry that consumes the very resources it seeks. It does not create beaches but exploits them; it does not generate cultural heritage, yet uses it as a resource. Moreover, tourism as an industry was specifically developed to manage the unpredictability that travel can bring. Its aim is to structure, systematise and ultimately standardise the experience so visitors can feel “at home” wherever they go. This need has a globalising effect that gradually strips places of their unique character.

The second paradox is that the world we live in has become touristified. Tourism is everywhere; it dominates newspaper front pages and has become a topic of social, political, economic and personal interest. It is no longer an isolated phenomenon, but an experience embedded in daily life. It is a force that reshapes places, spaces, cities and cultures, helping to explain a range of globalising effects.

Examples such as real-time translation systems that allow us to communicate in our own language with people from other countries, influencer videos that shape our travel and consumption choices, and the Airbnb aesthetic that influences our sense of what is “pleasant”, all show how tourism has become a key reference point for understanding how globalisation works, as anthropologist Miguel Antonio Nogués-Pedregal points out. In a short article we co-authored with anthropologist Saida Palou, we described it as a refractor – a mirror of society, a laboratory for observing the emergence of new meanings and social practices.

Digital nomads and the new mobility of tourism

One example of this are digital nomads, whose mobile lifestyle reflects the rise of remote working, allowing people to disconnect from offices and travel while taking their work with them. This phenomenon helps us understand how forms of tourism mobility are both a product and a driver of social change, in this case, the effects of the digitalisation of the economy. Digital nomads are knowledge workers who, thanks to technology, can work from anywhere in the world. For them, tourism is a way of life. They have a wide range of jobs and profiles: they can be freelancers, employees or entrepreneurs. They work across various fields – from translation to artificial intelligence development – as long as the activity can be done remotely and with a computer.

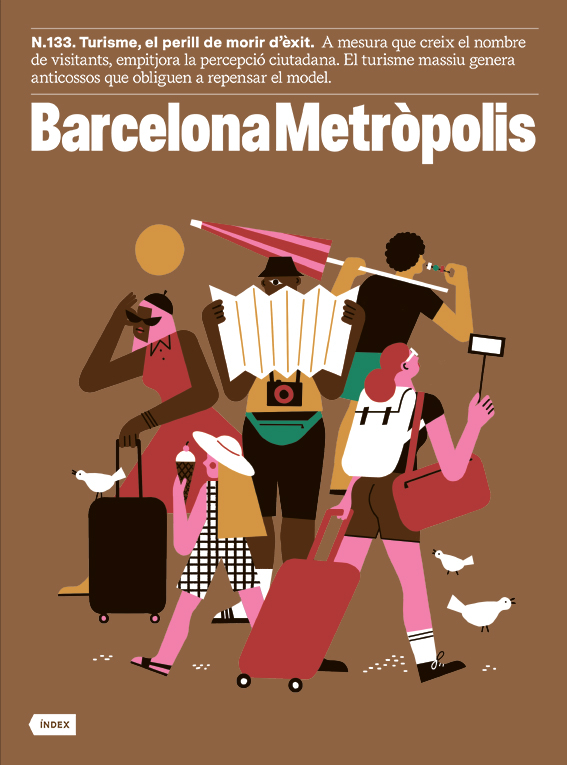

Ilustración © Irene Pérez

Ilustración © Irene PérezThey come from capitalist countries, meaning they usually have strong passports and a higher purchasing power than the local population. They look for good internet connectivity, a favourable climate, a welcoming local atmosphere, quality services and a reasonable cost of living. One common practice among them is geographic arbitrage: they choose locations where the cost of living is lower than in their home countries, allowing them to maximise the purchasing power of their income, which is earned in stronger currencies. This economic strategy is similar to the offshoring of production used by multinational companies.

Digital nomads are typically medium- to long-term visitors, although they are not immigrants, as they usually stay only for the duration allowed by a tourist visa (up to 90 days within the Schengen Area). Some may settle as permanent residents, but it is more common for them to practise multilocal residency, moving between various locations without a fixed base. They should not be confused with expats, a term often associated with well-off and privileged migrants, typically contrasted with other, less privileged and often racialised migrant groups. Nor should they be confused with remote workers, who, despite working remotely, do not necessarily relocate frequently.

Culturally, digital nomads are a disruptive phenomenon, as their hybrid practices implicitly challenge conventional ideas of tourism, work and migration. Take, for example, what we understand by “tourism”. Traditionally (and with a few exceptions, such as business travellers), tourism has been an activity that excludes work: we go on holiday when we’re not working.

Digital nomads are a disruptive phenomenon, as their hybrid practices implicitly challenge conventional ideas of tourism, work and migration.

Tourism expanded in the post-war era as a result of the working class’s victory in securing paid holidays. Until now, the organisation of work has been the central framework around which we structure the why and how of travel: long weekends, summer holidays, Christmas… However, digital nomads challenge this traditional (Fordist) model of working nine to five in an office and taking holidays at set times. They take their work with them to their holiday destinations.

Language and politics are adapting to these new realities. The media is using neologisms like “workcations”, which reflect the idea of working from holiday destinations. In January 2023, Spain introduced a remote work (digital nomad) residence visa through the Startup Law, which allows non-EU digital economy professionals to reside in the country for up to five years. In professional realms, digital nomads challenge traditional career models, which have typically been based on the idea of a stable, linear career. Their practices point to a new way of understanding and engaging in work, one that prioritises personal fulfilment over social security.

The impact on local communities

A legitimate question is what the consequences of these new mobility practices might be for the cultural, economic and social dynamics of destinations, particularly cities. From a tourism behaviour standpoint, digital nomads represent an innovative demand segment: their stays are longer, and a niche of consumers is emerging that promotes more sustainable practices, offering significant potential for peripheral destinations. Nevertheless, they also bring with them new demands, such as the need for infrastructure that supports their productivity: excellent connectivity, workspaces and suitable socialising opportunities.

The freedom enjoyed by digital nomads also has its downsides. Their presence can lead to price inflation in certain services and affect the residential housing market, particularly in terms of rents and investment in second homes. Interestingly, although digital nomads are often seen as challenging certain capitalist accumulation models, they may, in fact, be the perfect embodiments of this ideology. Thanks to geographic arbitrage, they can avoid crises like the housing shortage or job insecurity, only to end up reproducing them elsewhere due to their relative economic power.

Their multilocal lifestyle calls for plug-and-play city models: destinations where they can quickly and easily adapt.

Moreover, their multilocal lifestyle calls for plug-and-play city models: destinations where they can quickly and easily adapt, find comfort without disrupting their productivity, or stay for three to six months before moving on. In this way, digital nomads amplify the globalising effects of tourism, as they promote the standardisation of the destinations that host them. They are travellers seeking a cultural experience, but one softened by the conveniences of the hospitality industry. Although they may say they wish to immerse themselves in local culture, they often end up staying within their own circles, creating bubbles, as their primary need is to find a sense of community and avoid isolation. These bubbles often emerge from language or cultural barriers that prevent deeper engagement with the destination. Living in many places also means not having roots and feeling like you do not belong anywhere. This is the story of the highly individualised nomadic subject. Finally, a crucial point is the impact that these new residents have on the communities they join, particularly regarding key aspects of the social contract, such as political participation and tax contribution.

In conclusion, the phenomenon of digital nomads highlights the complex intersections between new forms of mobility and emerging work cultures, shedding light on their impact on the social, cultural and economic dynamics of destinations. While they present opportunities to diversify the tourism offering, they also bring challenges that can affect the social fabric of local communities. It is essential that both digital nomads and destinations find a balance between adapting to these new realities and preserving the quality of life for residents, in order to address the paradoxes of this era of global mobility.

References

D’Eramo, M. El selfie del mundo. Una investigación sobre la era del turismo. Anagrama, Madrid, 2020.

Mancinelli, F. “Digital nomads: freedom, responsibility and the neoliberal order”. Information Technology & Tourism, 22, 417-437. 2020. via.bcn/Yzt650TZxgq. Open in a new window

Nogués Pedregal, A. M. “El turismo como contexto”. Disparidades. Revista de Antropología, 75(1), e001c. 2020. via.bcn/ZKMO50TZwcK. Open in a new window

Palou Rubio, S. and Mancinelli, F. “El turismo como refractor”. Quaderns de l’Institut Català d’Antropologia, 32, 5-28. 2016. via.bcn/EVeC50TZwZv. Open in a new window

The newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter to keep up to date with Barcelona Metròpolis' new developments