Tourism and emotional response: A matter of perception

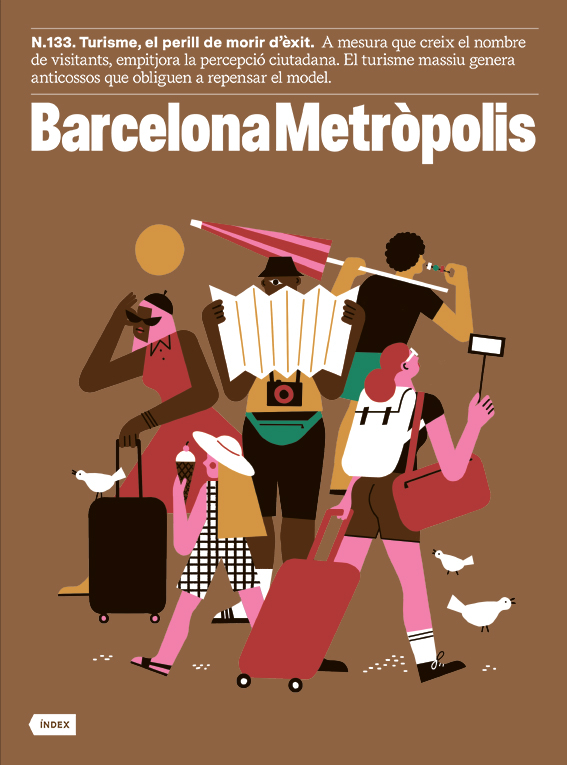

Tourism: The danger of being too successful

- Dossier

- Jan 25

- 11 mins

The massive influx of visitors is transforming the city. However, when residents are asked about tourism, opinions are often polarised. Some view it as a source of prosperity, while others see it as a source of problems. The response is emotional, but what factors shape citizens’ perceptions? And what do we know about how individual characteristics influence the way residents relate to tourism?

Tourism is an undeniable urban reality. Cities like Barcelona are being transformed by an activity driven by powerful forces such as global mobility, mass consumption, platform capitalism and the increasingly blurred boundaries between work and leisure. Clearly, the transformation of cities through tourism is a physical one, and it has happened so quickly that today’s grandparents can tell stories of a city – not the monumental one, but the real one, grounded in the neighbourhoods – that their grandchildren have never known. However, there is also a mental, more personal transformation, shaped by perceptions and subjectivities, that affects how we relate to our surroundings. In fact, collective reflection on tourism in the city has been much more prominent than individual reflection. Of course, we are influenced by our social class, social group and cultural background, but individual factors, such as personality, worldview and character, also influence how we perceive reality.

If we focus on tourism, these pre-existing views that define us as individuals act as intermediaries in relation to tourism stimuli, shaping attitudes and behaviours that vary from person to person. Understanding this can have significant implications for how we manage tourism in the city, viewing it not only as something that affects groups but also individuals. So, what do we know about how individual factors influence the relationship we, as residents, have with tourism in our cities?

Generally speaking, we can identify two main theoretical frameworks or approaches that explore this phenomenon. On one hand, there are theories that explain it as the result of weighing up the pros and cons. The most representative of these is social exchange theory. According to this perspective, people make a rational assessment, weighing up the benefits tourism brings against its drawbacks. This stocktaking is always shaped by our individual interests and perspectives.

This perspective helps explain why, when asked how tourism is perceived, opinions can be highly polarised among residents of the same city, or even the same neighbourhood. For some, tourism may be seen as a source of income, or they may not consider it a problem because they don’t experience its effects directly, or because it doesn’t impact them personally. On the other hand, for others, tourism can be seen purely as a source of problems, either because it doesn’t provide them with any income or because they have more frequent exposure to it.

A second framework, in which the theory of emotional solidarity is particularly important, suggests that certain individual characteristics act as intermediaries in our relationship with tourists. These theories focus not on the relationship between the community and tourism, but rather on the interaction between individuals (residents and tourists). Empathy, friendliness and a hospitable nature are factors that differ from person to person and can help explain whether attitudes towards tourists are more hostile or more friendly. Conversely, there is also the perspective that tourists have of the residents in the places they temporarily visit. To simplify, in the rest of this article, I will refer to the concept of emotional response to explore these two psychosocial perspectives on attitudes towards tourism and tourists.

How we perceive tourism through emotions

What do we know about the emotional response of Barcelona’s residents to tourism? I will address this question shortly. But first I would first like to emphasise that emotional response is not a substitute for understanding urban tourism, but rather a complementary approach that adds new dimensions and nuances to our social perspective. In this way, it enriches the broader explanations and interpretations of how people perceive tourism and its impacts. This perspective is relatively new, and has, until now, been somewhat overlooked, but it is increasingly attracting academic interest and gaining attention in tourism management.

Even so, the intersection between the collective and the individual remains largely unexplored in the field of urban tourism. Much like the absence of a universal theory to explain the universe – one that connects the workings of the very small (quantum theories) with the very large (Einsteinian theories) – we still don’t fully understand how the social perspective aligns with the personal one. In other words, we can’t say for certain whether the collective view of tourism results from a sum of individual, independent reasoning, or whether individual perspectives are shaped by collective trends. For instance, through the narratives of urban social movements and neighbourhood associations, or through the construction of social legitimacy strategies in the media.

On the other hand, let’s now take a look at what is happening in the city of Barcelona. In fact, we know very little, as there has been limited research on this topic. Still, a study published in 2022[1] offers some insights, as it examines the emotional response to the perceived situations of overtourism among residents of Barcelona. The results show that there are differences between residents and neighbourhoods. The study identifies three types of residents: those opposed to tourism (14.5% of the participants in the sample), those in favour of tourism (49.5%) and those who are neutral (the remaining 36%).

These are rough figures that convey much less than the more detailed breakdown of responses by neighbourhood. When we look at the distribution, the segments vary quite significantly. In neighbourhoods and districts with higher tourist pressure, such as Barceloneta or Ciutat Vella, those opposed to tourism make up a third of the total, while in less touristy areas like Sant Andreu or Horta, only 7% are opposed. This is entirely logical and doesn’t need much further explanation.

It is more interesting to explore why emotional responses differ between people who share both time and space in the city. When we face a stressful situation, especially one that persists over time, it triggers an effect likely linked to an atavistic response tied to the reptilian parts of our brain, which are designed to protect us in risky situations. It’s not that we produce more adrenaline when we see a tourist, but rather that the phenomenon is interpreted through a community lens, creating a dichotomy (them/us or outsiders/community members) connected to territorial control mechanisms.

When individuals identified as outsiders within the community are associated with negative impacts and stress, this can be seen as a loss of territorial control by the community. If the sense of control over one’s everyday spaces and places diminishes, concern increases, and negative emotions may develop towards the intruding phenomenon. But who is the target of the emotional response when it is negative? The same study addresses this question, asking residents how they perceive both tourists and tourism. The results are clear: the emotional response to the figure of the tourist or the feeling of encountering one on the street is generally much less negative – and in most cases more positive than pejorative – compared to the perception of tourism as an activity in the city.

If the sense of control over one’s everyday spaces diminishes, negative emotions may develop towards the intruding phenomenon.

Collective perspectives and personal opinions

To further interpret the findings, I draw on data from another unpublished study. In Anna Soliguer’s doctoral thesis,[2] the emotional responses of residents in Barcelona are compared with those of residents in Lloret de Mar. The same questions produce different emotional responses in each city, with those from Barcelona being consistently more negative than those from Lloret de Mar. These results raise some interesting interpretative hypotheses.

As previously mentioned, it is possible that places and collective perspectives influence personal opinions. Could we argue that the historical context of tourism development and its longevity play a role in shaping these views? This seems plausible, though it will need to be verified through future research. Despite the postmodern frameworks that now govern analytical methods and categories, it may be necessary to revisit classical approaches, such as those from the Vidal de La Blache school of geography, with concepts like genre de vie and milieu de vie.

Perhaps it is still worth asking, more than a century after its invention, whether the way people live in cities – where tourism is part of the “natural environment” – is shaping how they interact with their surroundings and respond in specific ways according to their way of life. This is significant, as it has implications for how residents of tourist destinations integrate tourism into their collective identity.

Let’s begin to conclude. Emotional responses to tourism represent a key area of interest for understanding the dynamics within the urban ecosystem: how the impacts of tourism (stimuli) are received by the various social groups that inhabit it, and the behaviours and attitudes they produce towards tourism and tourists. It is important to understand that emotions do not simply trigger reactions but can shape deeper attitudes that influence decision-making or aspects of identity, when mediated by feelings of rejection or nostalgia towards changes in the urban landscape.

Feeling comfortable in a place can also play a significant role in deciding whether to leave or stay. As research in this area progresses and previously unknown aspects emerge – meaning its predictive power increases – the emotional response should be incorporated into the future planning and management of tourism in the city. While this is not easy to capture, studies show that this response exists and helps to explain individual attitudes that can be just as powerful as those based on social or collective factors. In fact, many of the key issues in the current debate about how the city should relate to tourism are linked to this.

Examining emotional responses can, therefore, make a valuable contribution to understanding these issues. To give some examples, the ecological transition, the evolution of environmental thought and the subsequent debate on the limits of growth and degrowth require social and political coordination, but they also have a significant foundation in pro-environmental attitudes, which are shaped by personal experiences.

Tourism-phobia, which was the subject of intense debate a few years ago with a distinct ideological focus, and the current debate on touristification, can also be partly explained by individuals’ emotional responses. When overtourism and tourism pressure persist over time, they can be clearly understood from an emotional perspective at the individual level. These, along with other factors, influence how we manage both our personal and collective resources in the pursuit of a city that promotes greater happiness, reduces the stress caused by tourism, and improves physical and mental health, as well as subjective well-being. Therefore, it would be valuable for new urban and tourism policies to start considering the impacts of tourism through this psychosocial lens.

[1] González-Reverté, F. “The Perception of Overtourism in Urban Destinations. Empirical Evidence based on Residents’ Emotional Response”. Tourism Planning & Development, 19:5, 451-477. 2022.

[2] Soliguer Guix, A. La construcció psicosocial de l’actitud de la comunitat local davant el turisme: turismefòbia, protesta turística i resposta emocional [The Psychosocial Construction of the Local Community’s Attitude Towards Tourism: Tourism-phobia, Tourist Protest, and Emotional Response]. Interuniversity Doctoral Thesis in Tourism, Universitat Oberta de Catalunya. Supervisor: Francisco González Reverté. 2023.

Recommended reading

Ciudades efímerasFrancesc González Reverté & Soledad Morales Pérez. Editorial UOC, 2013

Ciudades efímerasFrancesc González Reverté & Soledad Morales Pérez. Editorial UOC, 2013 A propósito del turismo Salvador Anton Clavé & Francesc González Reverté. Editorial UOC, 2010

A propósito del turismo Salvador Anton Clavé & Francesc González Reverté. Editorial UOC, 2010

The newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter to keep up to date with Barcelona Metròpolis' new developments