Dynamics and challenges in urban tourism

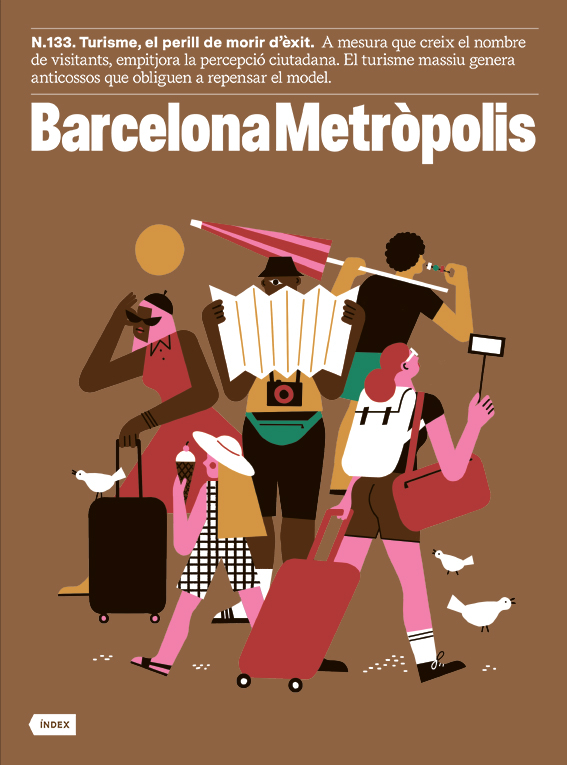

Tourism: The danger of being too successful

- Dossier

- Jan 25

- 11 mins

Residents’ perception of the expansion of urban tourism, which is increasingly blurring the boundaries between tourist and local spaces, is steadily worsening. As a result, cities like Amsterdam and Copenhagen have introduced measures to counter its negative effects. While some of these measures are proving more successful than others, their true impact will only become clear over time.

Cities have always played an important role in tourism, but the emergence of a specific “urban tourism” sector is relatively recent. In southern Europe, for example, tourism urbanisation processes in the 1960s and 1970s focused on coastal resorts with relatively small resident populations. The expansion of tourism was supported by new urban development, which included the construction of new hotels and apartment blocks close to the sea.[1]

Most debates surrounding tourism development at this time centred on the environmental effects of increased urbanisation. In northern Europe, major cities began to gain recognition as centres of cultural tourism in the 1980s, when economic pressures encouraged de-industrialising cities to shift from manufacturing to service industries. Cities also became increasingly important as hubs for business tourism, with many new conference and exhibition centres being developed in the 1980s and 1990s.

By the turn of the millennium, a recognisable tourism sector had, therefore, become established in many urban areas across Europe. The development of tourism activities was, nevertheless, relatively separate from the everyday life of the city and its residents. Enclaves of tourist accommodation were often clustered around major transport hubs or near the city centre’s entertainment districts. This situation was described by Gregory John Ashworth and John E. Tunbridge in their model of the ‘Tourist-Historic City’.

As urban tourism expanded, however, divisions between tourist spaces and local spaces began to dissolve. The study City Tourism & Culture: The European Experience, conducted in 2005 by the European Travel Commission / UN Tourism, indicated significant growth in urban tourism, with overnight stays in European cities rising by 38% between 1993 and 2000. This also attracted the attention of urban policymakers eager to capitalise on high-spending cultural tourists. Some cities, such as Barcelona, also harnessed event-led tourism development, with major events such as the 1992 Olympic Games and the Gaudi Year in 2002 attracting visitors and supporting placemaking initiatives.[2] The success of these initiatives encouraged Barcelona to stage the Universal Forum of Cultures in 2004, a UNESCO-branded gathering on cultural dialogue.

Tourism was initially viewed in a positive light by policymakers and residents alike. Yet, 2004 marked an early indication of changes to come. The Forum generated negative sentiment among many residents who felt excluded by high entry fees, inflated food prices and corporate sponsorship. The Forum provided early warnings of cracks in the post-Olympic ‘Barcelona Model’.

A change in perception over the years

Growing concern among policymakers led Jordi Portabella, the Councillor then responsible for tourism, to commission research on resident attitudes to tourism in late 2004. However, the research showed that Barcelona residents were still highly supportive of tourism, particularly cultural tourism. Over 90% supported further tourism growth and 91% were in favour of developing cultural tourism. Although the initial research results may not have aligned with what the politicians had anticipated, they decided to continue monitoring resident attitudes. This ongoing research was incorporated into the Observatory of Tourism in Barcelona, and this research provides a unique longitudinal picture of the relationship between tourism and the city and shows how attitudes have changed as urban tourism has grown.

Illustration © Irene Pérez

Illustration © Irene PérezAround 70% of residents supported the idea of Barcelona attracting more tourists in 2005 and 2006. However, this figure dropped sharply to around 50% in 2007, reflecting growing unease with the pace of tourism growth. Between 2007 and 2012 support for tourism growth rose again, likely influenced by the economic crisis during those years. Since then, tourism support has steadily declined, accompanied by a growing proportion of residents who believe that Barcelona has reached its limit in terms of accommodating tourists. The tipping point came in 2016, when negative attitudes towards tourism became the majority. Since the pandemic, anti-tourism sentiments have remained high, with over 60% of residents indicating that the city had reached its limit, a level comparable to that in 2019.

Changing attitudes also affected behaviour. When asked about contact with tourists, about 60% of the population had regular contact with tourists in the city in 2011. This rose to 70% by 2014, as tourist numbers grew. But from 2015 onwards, contact with tourists declined, suggesting that locals were actively avoiding tourists and tourist areas.

This analysis shows that concerns about urban tourism growth predated the arrival of Airbnb in Europe in 2011. Nevertheless, Airbnb has come to represent many of the challenges associated with urban tourism. It pioneered a new model that integrates tourism into the very fabric of the city. Tourists are no longer confined to enclaves with hotels and tourist-oriented facilities but can now penetrate residential neighbourhoods. This shift transformed the old ‘Tourist-Historic City’ model of the 1990s into the modern ‘live like a local’ city. Visitors flocked to experience local life in cities like Barcelona, Lisbon and Berlin, facilitated by Airbnb and new ‘low-cost airlines’ like EasyJet and Vueling. As a result, the cost of reaching and staying in popular cities dropped dramatically, ushering in what was termed the ‘New Urban Tourism’.[3]

In 2004, Barcelona received 4.4 million tourists. By 2019, tourist arrivals had grown to 20 million.

New Urban Tourism thrives in ‘cool neighbourhoods’ offering an appealing mix of bars, restaurants and local culture. This trend is tracked by the Time Out survey of the ‘World’s Coolest Neighbourhoods’. The 2024 survey lists Notre-Dame-du-Mont in Marseille, Mers Sultan in Casablanca and Pererenan in Bali as the top three trendiest neighbourhoods worldwide. Barcelona has featured six times in the ranking over the past seven years, including neighbourhoods such as Gràcia, El Clot and Poblenou. These are areas that previously saw no significant tourism flow.

The influx of visitors has added to the pressure on urban space. In 2004, Barcelona received 4.4 million tourists, with a resident population of 1.6 million. By 2019, tourist arrivals had grown to 20 million for a population of 1.7 million, resulting in an increase in the ratio of tourist arrivals to residents from 2.75 to 11.8 – more than a fourfold increase. Numbers fell during the pandemic, but with 15.6 million tourists in 2023,[4] the ratio was still 9.2 tourists for every resident. This growth cannot be attributed to Airbnb alone; it also reflects the growth of hotel accommodation and budget airline seats. In other words, it is the result of a tourism model based on increasing visitor numbers, rather than maximising visitor spending or focusing on particular visitor groups.

Some comprehensive measures

This kind of tourism development has recently come under fire in other cities. Protests in Tenerife, Alicante, Ibiza and other places have called for a change in the tourism model, which some residents blame for issues such as rising rents, higher prices, community decline and environmental degradation. In response, some cities have introduced measures to address the new challenges of urban tourism. Among the most comprehensive are those implemented in Amsterdam.

Measures to control tourism in this Dutch city were introduced through the Tourism in Balance policy, developed in 2019 after 30,000 residents called for a new approach to tourism policy. The city now imposes a 12.5% tax on tourist accommodation, the highest rate in Europe. Regulatory actions have included restrictions on Airbnb, reducing listings from 16,648 in March 2021 to fewer than 3,000 by October 2021. The opening of new hotels was also banned. In addition, the city has implemented bans on smoking joints and drinking alcohol in public spaces in central areas, and outlawed beer bikes and large tour groups. Amsterdam has also sought to distribute tourism more evenly across the city by encouraging visitors to explore new neighbourhoods and regional attractions. Efforts also include de-marketing campaigns aimed at certain groups, notably young British men, using social media to discourage undesirable behaviour.

However, it remains unclear whether the measures adopted in Amsterdam or other cities are having much impact. Notwithstanding the rising tourist taxes, visitors continue to arrive. In 2023, Amsterdam recorded over 22 million overnight stays, despite the Municipality agreeing to limit overnight stays to 20 million. A recent report on the implementation of the tourist tax concluded that the tax would need to be about three times higher to have a real impact on visitor numbers. Meanwhile, the supply of Airbnb listings has risen again, reaching almost 10,000 in 2024. Although this is lower than the levels seen before the new controls, it is gradually returning to previous figures. New hotels also continue to open, as development licences were granted before the ‘hotel stop’ was introduced in April 2024.

Attempts to spread visitors to areas outside Amsterdam have also had little effect, according to tourism expert Stephen Hodes. He argues that visitors who stay on the city outskirts merely free up space in the city centre for more tourists. Those staying outside the city typically travel into the city daily, further adding to the pressure on transport services.

With economic, regulatory and spatial controls seeming to have had little impact in Amsterdam so far, there may be a need for more creative approaches. Copenhagen has distinguished itself from other cities by adopting a series of measures based on persuasion rather than direct controls. The city introduced the Tourism for Good strategy in 2021. This takes a broader approach to tourism development, with sustainability goals based on three pillars: tourism should accelerate the green transition, tourism should create enriching encounters and tourism should create larger socio-economic value for more people. As monitoring only began in 2022, it is still a little early to tell whether this strategy will succeed. However, Wonderful Copenhagen, the City’s Destination Marketing Organisation, is making efforts to get the tourism industry on board with the strategy. They have developed a ‘Legacy Lab’, aimed at fostering more positive long-term impacts from city events.

We will have to wait and see whether the Copenhagen efforts make any difference to the volume or quality of urban tourism. Tracking trends in urban tourism has been particularly challenging due to the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, which drastically reduced urban tourist flows. Nevertheless, initial tourism data for 2024 suggests that most cities have now recovered or exceeded 2019 visitor levels. The average increase in visitor numbers for cities reporting to the TourMIS database[5] was 5.5% during the first eight months of 2024. Similarly, the number of visitors to tourist attractions in European cities rose by an average of almost 14% in 2023. These figures seem to indicate that cities are still experiencing the effects of ‘revenge tourism’ in the wake of Covid, with consumers eager to seize opportunities to travel. The evidence suggests that urban tourism will continue to grow, and with it, the associated pressures, which will likely be further exacerbated by rising resident populations in many cities. In the future, planners will have to devise even more creative solutions to tackle the inevitable challenges.

References

Gerritsma, R. “Overcrowded Amsterdam: Striving for a balance between trade, tolerance and tourism”. Overtourism: Excesses, discontents and measures in travel and tourism, 125-147. CAB International, Wallingford, 2019. via.bcn/qLnK50Uo51x. Open in a new window

Richards, G. Rethinking Cultural Tourism. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, 2021. via.bcn/MZ8k50UnCSq. Open in a new window

[1] Clavé, S. A. and Wilson, J. “The evolution of coastal tourism destinations: A path plasticity perspective on tourism urbanisation”. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(1), 96-112. 2017.

[2]Richards, G. “Placemaking in Barcelona: From ‘Paris of the South’ to ‘Capital of the Mediterranean’”. MNNieuws, 8-9. 2016. via.bcn/eAxq50UnE2C. Open in a new window

[3]Füller, H. and Michel, B. “‘Stop Being a Tourist!’ New Dynamics of Urban Tourism in Berlin-Kreuzberg”. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38(4), 1304-1318. 2014.

[4] Observatory of Tourism in Barcelona, 2024.

[5] TourMIS. City tourism in Europe recovery monitor. 2024. www.tourmis.info

Recommended publications

Small cities with big dreams Greg Richards and Lian Duif Rouletge, 2018

Small cities with big dreams Greg Richards and Lian Duif Rouletge, 2018 Eventful cities Greg Richards and Robert Palmer Rouletge, 2010

Eventful cities Greg Richards and Robert Palmer Rouletge, 2010

The newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter to keep up to date with Barcelona Metròpolis' new developments