Kao malo vode na dlanu (Like a Little Water in the Palm of the Hand), a project about love in Serbia

Dates: 15 February to 28 April 2019

Exhibition Opening: Thursday 14 February, at 19.00

Where: 3rd Floor

The Contemporary Art Centre of Barcelona - Fabra i Coats presents the exhibition Kao malo vode na dlanu (Like a Little Water in the Palm of the Hand), a project about love in Serbia, by Mireia Sallarès, which explores the problems attaching to amorous thinking.

During the exhibition period the seminar Love for what? Changing love to change everything? will be held. Free seminar with limited number of places. The sessions will be held in the exhibition space at the Contemporary Art Centre of Barcelona – Fabra i Coats and in one instance at the Filmoteca de Catalunya. For compulsory advance registration, either for the entire seminar or for individual sessions, please email centredart@bcn.cat.

[ASSAIG OPUSCLE]

Joana Masó (curator)

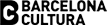

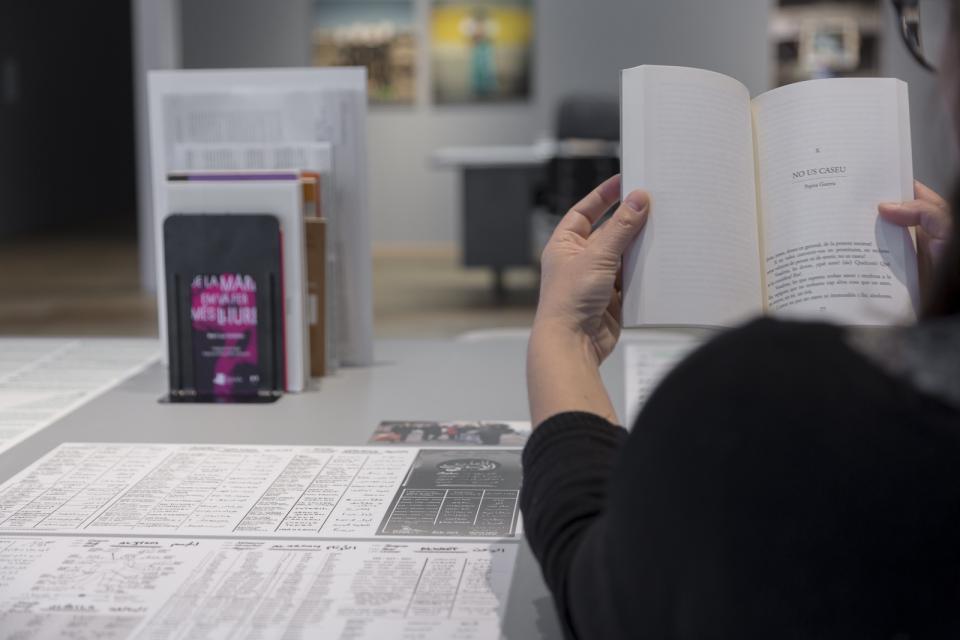

Why does an exhibition about love include old gloves, falling-down façades and damaged photographs? Why do we see faces hidden by worthless odds and ends or hands holding crumpled photocopies in the wastelands of our refugee camps? Why does a film about love in Serbia talk about the relationship between workers at a privatised communist collective factory and the organisation Učitelj neznalica i njegovi komiteti (The Ignorant Schoolmaster and His Committees), a collaboration that ultimately sought to denounce capitalism before the International Criminal Court in The Hague for human trafficking and the new forms of slavery? Why, in the course of this investigation into love, is the poem ‘Đubrište’ (‘Rubbish Dump’), by Serbian author Danilo Kiš, translated into Catalan? And why is the love story that is told accompanied by trash?

This project by Mireia Sallarès (Barcelona, 1973) began during an investigation into truth in Caracas in 2011. This was the origin of the Trilogy of Trash Concepts; prolonged researches into life in relation to the doubtful political prestige of concepts such as truth, love and work. Someone told her the story of Eros, son of Penia, love as the child of poverty, of a beggar. Before long this precarity of love was resonating far beyond material precarity: love as a trash concept served to open up the question of everything that counts for nothing, that is looked down on or undervalued in the common imaginary regarding love in its effect on our lives. All (that, those) we collectively drop, throw away, abandon or neglect, as the dictionary reminds us, we use the word ‘trash’ of someone of no value, worth nothing.

But trash is also what needs to be recycled, decolonised, reincarnated. And this is something that we can only undertake collectively. Love as a trash concept resonates with a long philosophical tradition revived by the emancipation movements of the 20th century in relation to the economy of love and the recyclable or unusable condition of love in political terms. What is the amorous thinking we have incorporated, who exploits it and who abuses it? What inequalities does it generate and what withholding of recognition does it entail? Is love, when all is said and done, a passion of domination or of emancipation? Does it contribute to the reproduction of inequalities or can it subvert them? Can it be a productive force or only reproductive? Is it a simple passion or a democratic passion, with libertarian roots? As a way of relating to these questions, in the film-conversation around which the exhibition is articulated and in which only two people seem to be talking, many voices from different places are heard: the interpretation of the Yugoslav Wars, the transformation of ownership since communism and the transition to capitalism, the critique of romantic love, the anarchist legacy and feminist anthropology, the condition of the stranger and the tragedy of the refugees, psychoanalysis and the fiction of a police interrogation in which art calls into question the meaning of its practice.

In ‘Mal d’amore’ (‘The Pains of Love’), one of the essays accompanying Mireia Sallarès’s investigation, the militant anarchist thinker Errico Malatesta spoke of the trials of love as a way of talking about freedom and the trials of freedom as a way of talking about love. He said we have no solution for either, but he also wrote that the freedom to do what we want is meaningless if we don’t know how to want or love what we want. Malatesta not only spoke of how inseparable the work of love is from the work of freedom, but also that the freedom to do what we want is only free when we know how to want, how to love. We are only free when we know how to produce esteem: when we know how to value what to others may be worthless, count for nothing or next to nothing — like trash. Otherwise, as Fina Birulés has written, being free to do only what you want is more like loneliness than freedom.

The water in the palm of the hand of all those holding up objects of little value in the photographs that accompany this project on love, holding up this freedom to love. Helena Braunjštain, the first Serbian that Mireia Sallarès met, ten years ago in Mexico, and the author who has accompanied this project from its inception, recalls the words of Jacques Derrida, who said that any treatise on love must be an act of love, an act with love. This extended investigation by Mireia Sallarès shows what can happen to art when it lets itself be pervaded by an amorous practice. Derrida also spoke of the dense forest of prohibitions, discriminations, codes, scenarios and positions we must make our way through in order to cease separating love from other affects such as charity or friendship. What the many voices and stories in Mireia Sallarès's project lead us to think about is undoubtedly this amorous practice in which love extends itself to where it was not expected. And where that dense forest is never far away.

Every Saturday at 18.00 and Sundays at 12.30 guided tours of the exhibitions.

Free entrance.